Writing about genetically modified food last week got me thinking about Humanity’s history of mutating the plant world to its gastro-nutritional whim. It is those directed mutations that created civilization itself. For instance:

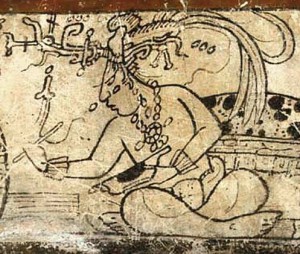

In the beginning, the gods of the Maya created humans out of mud. But the mud men squinted at the world, and could not take it in. They could not move to chase game or to seek shelter, and their thoughts were clogged. The rains washed them away.

The gods then made humans out of wood. These men could speak and see and move. On all fours, they climbed through the jungle canopies and rambled over the valleys, but they failed to honor the gods as the gods saw fit. Perhaps their taste of freedom was too complete. Perhaps they razed the jungles where their flesh was found. The gods thus destroyed them.

And so the gods tried a third time. They made Man out of maize. And this Man was in harmony.

The Aztecs, building their origins on the Mayan foundation 1000 years or so later, attributed five creation attempts to the gods, rather than three. Only in the fifth generation did Man eat maize. In the two previous generations, he ate a grain named teosinte. And the difference between the first, a wild grass, and the latter, a creation of Humanity, made all the difference in the world.

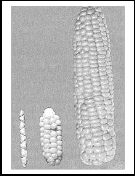

Teosinte is short and thin and has two rows of kernels protected in tough membrane casings. Wild animals eat the grass, and the casings help the kernels make it through the beast’s intestinal tract intact so that they may act as seed for more teosinte.

A single gene controls the size of these casings, and a small mutation can leave the kernels exposed. This is bad from the plant’s perspective because the foraging animals that eat the mutants can use the kernels for food, rather than the plant using the animals for transport and reproduction. But what is bad for the grass proved vital for Humanity. It is what, in the Western Hemisphere at least, turned foragers into farmers.

This trio of teosinte, proto-maize, and maize was taken from 'An Edible History of Humanity,' by Tom Standage, the book that was my source for much of this post.

Early proto-farmers, starting sometime around 8,000 B.C., collected mutated teosinte because the exposed kernels were easy food. The bigger those kernels were, the better, and it was kernels from those individual grasses that were saved and planted the following year. Over time and through ongoing human selection they grew big enough that plant propagation by humans, rather than the whims of nature, was required, lest the big kernels of a big plant fall and sprout into more big plants, everything ultimately choking itself out in competition for water and nutrients and sun.

By 3,700 B.C., Humanity had created our Corn, a food grain whose propagation turned nomadic bands into peopled cities, whose nutritional plenty allowed for a population explosion, and whose entire existence relied on Us. Corn cannot grow in the wild. We made it, and it needs our husbandry to survive. (The University of Utah has a pretty great diagram of the process.)

Our archeologists have found ancient cave paintings and fossilis that reveal the progression of cobs from half-an-inch to eight inches in length.  Our geneticists have deduced that we created our Corn from a type of teosinte named Balsas. Balsas hails primarily from central Mexico and the Mayan region. The only remnant of teosinte in our corn is the ghostly descendents of those original protective casings. They are the filmy kernel sheaths that get stuck between our teeth each summer when we eat corn on the cob.

Our geneticists have deduced that we created our Corn from a type of teosinte named Balsas. Balsas hails primarily from central Mexico and the Mayan region. The only remnant of teosinte in our corn is the ghostly descendents of those original protective casings. They are the filmy kernel sheaths that get stuck between our teeth each summer when we eat corn on the cob.

And so Man survived and thrived. He took a grass created by the gods and made creative use of one of its mutations, also sparked by the gods, to sustain himself. He had no need to splice genes and inject the synthetic. He only needed to detect the tools the gods gave him and wield them skillfully. And from that partnership, wherein the roles were defined and humility and patience rewarded, food was made for All. Today, all varieties of teosinte are threatened with extinction.